Beginnings

In the beginning I read and read and read until I read for a BA in English Literature and Language at Wadham College, Oxford University.

Training

After Oxford I felt like a half formed thing.

I then went on to train as a director at Drama Centre London/Central St Martins and developed my theatre practice in relation to the work of Stanislavsky, Strasberg, Meisner, Malmgren, Hagen, Adler and other key performance practitioners. The training is actor focused - the actor and director share an intimacy, or ‘language’ that permits a certain intensity of experience in the rehearsal room; it's an influence that creeps into my rehearsal room still today. The training was systematically rigorous and rigorous about systems; it had its limitations and I wanted to go off and explore something less coherent, more curious, more disparate …

Teaching at RCSSD

My exploration lead me to … another institution. I worked as a visiting director and lecturer on the MA (Classical) Acting at Royal Central School of Speech and Drama for a number of years co-directing postgraduate students in classical texts - particularly Shakespearean drama. Here’s me directing on the set of a production of Much Ado About Nothing - one of the many Shakespeare texts I directed here. As an emerging director I developed a real sense of stagecraft as I worked on these large, ensemble company pieces. Working with Shakespeare’s texts totally freed my practice up (contrary to all my expectations) and I found that kicking off the ache of naturalism and the subterfuges of subtext liberating. My approach in the rehearsal room became more improvised, more intuitive. Direct address means that an actor looks straight back at you when you share that space with them - the relationship between myself and the performers changed again.

And all of those slightly unfunny Shakespearean comedic characters got me thinking about clown.

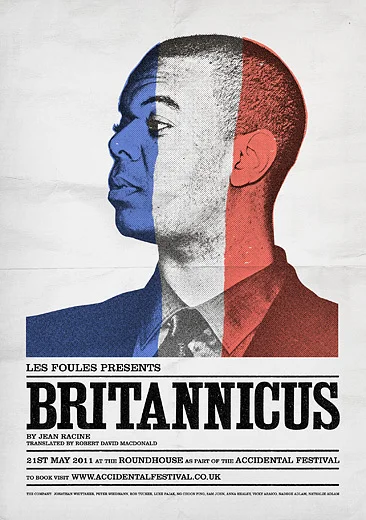

Clowns and Les Foules

I took some clown classes with Jon Davison, a clown. It seemed to me that clowning was quite a mechanised performance mode: clever and almost mathematical, performance with its own very clear logic. I realised that I was probably more of a clown in real life than in performance terms, so I decided to borrow some of its rules, and draw together what I had learnt at Drama Centre and developed at Central, and create a company with Nadège and Peter (see website for more about them).

We created Les Foules - a company whose name was a kind of bad Franglais pun. We started as we meant to go on.

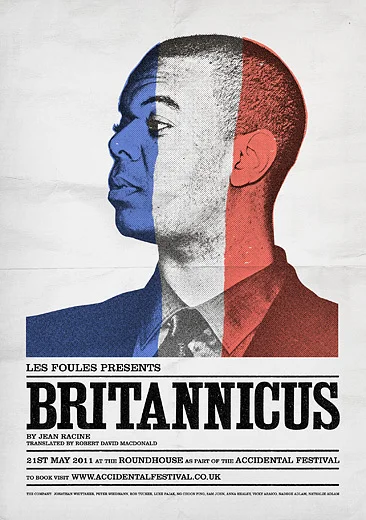

Our inaugural production was a clown version of BRITANNICUS by Jean Racine. We thought it would be funny to slap a figurative red nose on face of this gloomy French tragedy and to see how the tricky translation of Alexandrines held up under pressure.

It worked.

Image: Luke Pajak

#2 Boxed and Bagged

As we were building our company devised work and immersive theatre experiences were all the rage.

I wanted to know about these practices too and pitched for a slot at the Bush Theatre for a huge artist building takeover with Theatre Deli.

I spied a staircase that I liked the look of and wondered if we could create a piece with these stairs as the architectural backbone to the piece, both narratively and spatially. The up/down trajectory of the staircase made me think about non-linear entry points to a narrative, and I loved the idea of creating a piece that could be joined or departed from at literally any step of the way. Loosely influenced by William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, we created a piece around the freshly dead Augusta, an American from the deep south.

It was the first piece that I created that was self-consciously actor devised.

Every night we would take our audiences to the moon and back.

#3 Cymbeline

Cymbeline is well known for being one of those strange Shakespearean texts - moving in and out of fashion over decades: a play that holds a mirror up to our own natures in its wax and wane. In it, Imogen the King’s daughter, is scrutinised by a voyeur villain and audience as she sleeps exposed and naked, after which she undertakes a journey into the wilderness in cross dress. I wanted to play with flipping some of these famous scenes in literal representative way and move this iconic image of the sleeping Imogen from the horizontal to the vertical planes. Shakespeare’s stilled female corpses - from Hermione to Imogen - are so interesting to stage: imprisoned by the stillness they must perform as stoically as their gender.

This was a bombastic extravaganza production: a large, free wheeling doubled up cast, a beautifully scored piece played live, projections and video art adding a steam punk aesthetic all playing in the beautiful wood and brick casing of a converted Presbyterian church.

#4 Much Ado About Nothing

Shakespeare again. In Uganda. And another strange confrontation with women as living dead in Much Ado About Nothing.

Les Foules were invited to the National Theatre of Uganda to stage a production and work with Ugandan actors, many of whom had not had a training. So with this production I led a process that was part training, part rehearsal, and I explored elements of verse speaking, character work, physicality and basic stagecraft with the cast. The Ugandan actors were clear that central to this interpretation of the play must be the large Ugandan wedding. This seemed doubly appropriate as alongside our own rehearsals, the National Theatre in Kampala simultaneously hosted wedding after wedding after wedding rehearsal. Reality and art converged and the experience felt like a kaleidoscopic marital mise en abyme. These recurring wedding images inevitably seeped into the play, and the frozen snapshot wedding photo became the central image or tableau to shape this interpretation.

#5 Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone

In the murk and gloom of the tunnels under Waterloo station, a festival of nascent new work was beginning to make its name. At the Vault Festival, I too was travelling in a new direction, working on a piece of new writing that ripped and roared out of four brilliant female performers’ mouths. A truly strange and wonderful beast: Tobias Manderson Galvin’s own kind of verse tripped off the tongue of two neighing horse girls, botched beauty queens, and a performaing psychopath and her muse. It made sense, it didn’t. A male feminist megaphone of trash talk and politics performed and evolved by an all female team. This was a different kind of directing for me - narrative fading out to the periphery of the texts, political anger cased in allegory the form the message took. The Vault Festival loved it and awarded us the Origins Award for Outstanding New Work.

#6 When We Dead Awaken

With this show I was interested in the traditional artist/muse relationship that Ibsen explores here. The muse is, of course, feminine. Art is, of course, more interesting than life. Relationships do, of course, suffer under the tyranny of the artist’s way. All of these clichés abound here,but I wondered whether we could reroute some of the energy of the text and reenergise the debate at the centre of a drama in which the male gaze glowers heavily over the proceedings of the story. With its own images of petrification and mass, element and sculpture, I recreated the world of the Victorian spa resort using different textural mediums from plastic to clay to trap the transient inhabitants of that world.

CLICK for production page

#7 Crude Prospects

As a company we wanted to make a new work that explored and dramatised the global environmental crisis. We knew that making a piece of work of this kind was going to be tough. We looked into the philosophy of ecology, and the challenge of representation when it comes to the environment: the difficulty that people have in really imagining the abstract. I was interested in how we could make this crisis concrete on stage, and I didn’t want to make a piece of agit prop theatre. Our focus here was oil extraction in Alaska, and the specific cultures that collide in that territory: from scientists to cetaceans and back again. Here we explored the new frontier as a slick oil Western, mixing media and incorporating the filmic projections of another world.

#8 As the Waters Rose

After London and Crude Prospects I boarded a plane and landed in Montreal to take a riff on Crude Prospects to the Montreal Fringe. A new cast came together from the US, UK and Canada and together we explored the more intimate narratives of those affected by extreme weather and climate change. I hadn’t performed in a while but my imagination had been fired up by a scientific paper that explored the way certain charismatic megafauna become the poster animals for environmental causes. Polar bears get people excited and engaged, and I wondered what it would be like to have a relationship, of sorts, with one. I was also really pleased to evolve material from another show. It’s easy to be wasteful with even the written word, and here we used every last morsel from our previous show and reimagined it. As the Waters Rose was nominated for Best Production of the festival.

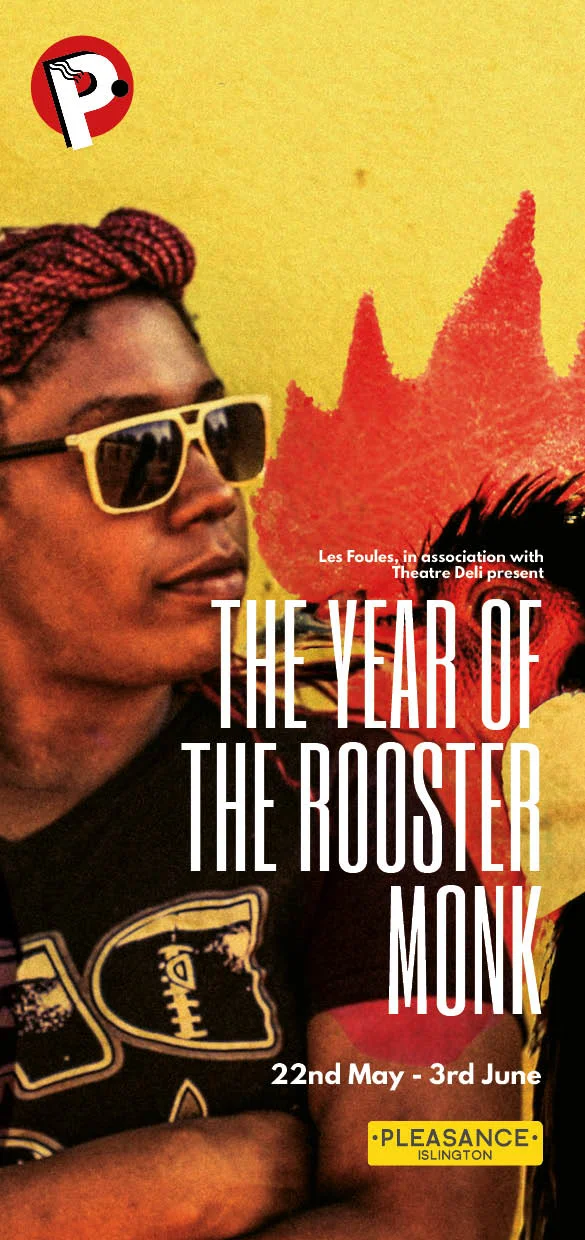

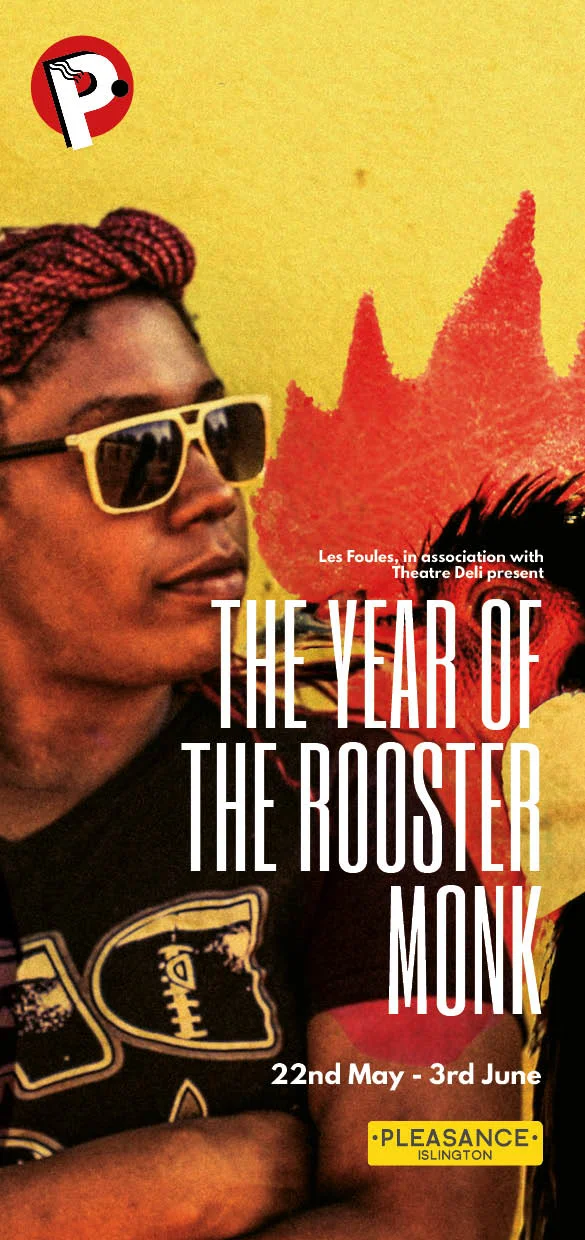

#9 The Year of the Rooster Monk

The one woman show. Everyone was doing them. Everyone IS doing them. And by February I was really interested to know what doing one was like too. They seem deceptively simple, compact acts of storytelling full of intimate narratives or virtuoso performance where the one becomes many. I’d worked with Giselle LeBleu Gant many times and we decided to collaborate on this together. Giselle wanted to explore Black Girl Magic, and at the time that we started to collaborate on this show, she was was moving out of the Harlem apartment she’d been living in most of her life. I found myself sculpting a story that drew on common millennial tensions and perspectives: Giselle’s story drew on race, gender, gentrification and the problem of being … a performer, and the piece stood at the crossroads of stand-up, clown, and storytelling, with elements of gig theatre creeping in and blurring the edges of how we say what we want to say.